Wetlands are a vital part of Nebraska's natural landscape, yet many people are unaware of their significance in the state's history. The Eastern saline wetlands once spanned over 20,000 acres, primarily in the floodplains and low-lying areas of Salt Creek, Little Salt Creek, Oak Creek, Oak Lake, Capitol Beach, and Rock Creek. These wetlands were integral to the development of Lancaster County and the surrounding region.

What are Saline Wetlands?

The Eastern saline wetlands of Lancaster and Saunders counties are among the most unique and at-risk wetland communities in Nebraska, out of the state’s four major wetland complexes.

Nebraska’s saline wetlands are characterized by saline soils and salt-tolerant plants, such as inland saltgrass. While the exact source of the salt is not fully understood, it is believed to result from groundwater flowing through rock formations containing salts from ancient inland seas. These wetlands are sustained by Dakota sandstone, the underlying bedrock along Salt and Little Salt Creeks.

The History of Salt Creek

Before Nebraska became a territory in 1854, the Salt Valley (now Lancaster County) was home to four Native American tribes. The Otoe and Missouri lived to the east, the Kansas to the south, and the Pawnee to the west.

The salt basin in Salt Valley was a significant resource for both indigenous peoples and animals, as they recognized the importance of salt in their diets. However, due to the area's susceptibility to flooding—being crossed by seven creeks—the indigenous people avoided establishing permanent settlements there.

During their 1804 exhibition, Lewis and Clark made note of Salt Creek, describing it as “A small river comes into the Platt called Salt River, the waters so brackish that it can't be drank at some seasons.”

Civil engineer Augustus F. Harvey, who surveyed Lincoln’s townsite, was optimistic about the salt industry in Lancaster County. In his pamphlet "Nebraska as It Is", he praised the area's salt springs, noting that the salt crystallized like fine table salt and could become a valuable resource. He saw these deposits as an important asset that could contribute to economic prosperity.

The first settlers to Lancaster County were drawn to the Salt Basin, which stretched as far east as Plattsmouth and Nebraska City. They believed the salt would lead to wealth and envisioned a thriving city powered by salt production. It's likely that the choice to place the state capital in Lincoln (formerly Lancaster) was influenced by the potential of salt manufacturing to boost the local economy. Early settlers were hopeful that salt production would create business opportunities and attract investment.

However, the salt industry never lived up to these lofty expectations. Mining and transporting the salt proved difficult, and there were legal challenges related to leasing the salt lands from the state.

J. Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day and father of the future Morton Salt Co. founder, played a role in transferring the salt basin land to John Prey, Lancaster County's first settler. In exchange, Prey granted warranty deeds to Morton and two other partners, including the land's original surveyor. Morton later challenged the state’s salt leases. While he lost at the local level, The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled in his favor.

Modern Saline Wetlands

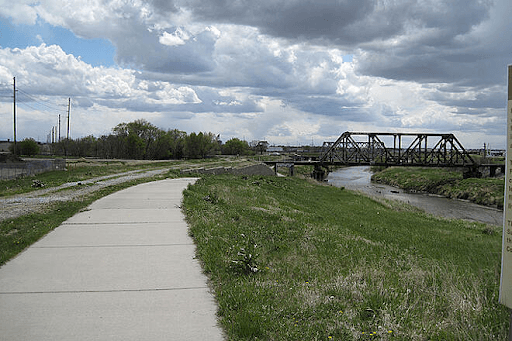

At one time, the Eastern saline wetlands covered more than 20,000 acres, but much of the land has been altered to accommodate the urban development of Lincoln and to prevent flooding. Today, less than 4,000 acres of saline wetlands remain, and much of this land is in poor condition due to draining, filling, and development for agriculture, housing, and businesses.

Saline wetlands do more than provide habitats for wildlife and plants—they also play a key role in water management. They help improve water quality, reduce flooding and soil erosion, and supply water. These wetlands filter runoff and control floods by storing water during heavy rains. Additionally, they offer recreational activities such as hunting, wildlife watching, and provide a peaceful escape into nature.

The Eastern saline wetlands are also home to species like the Salt Creek tiger beetle, which is found only in this region. The Salt Creek tiger beetle is both a state and federally listed endangered species, making the conservation of its habitat crucial.

In 2003, state and local agencies formed the Saline Wetlands Conservation Partnership to help preserve these unique landscapes. This initiative aims to protect the wetlands while balancing the needs of the local community. To ensure the health of Nebraska's saline wetlands, it’s essential for landowners, conservation groups, and government agencies to collaborate.

Explore Nebraska’s Wetlands

To learn more about the rich history of Lincoln and Salt Creek, visit the 15 different wetland areas in Lancaster and Saunders County listed on the City of Lincoln’s website, or explore the Lincoln Saline Wetlands Nature Center, located east of Capital Beach.

To learn more Check out other resources related to the Lincoln’s crucial Eastern saline wetlands:

Conservation Nebraska Webinar on Lincoln, Nebraska’s Legacy

Conservation Nebraska Restoring Eastern Nebraska's Saline Wetlands

Saline Wetlands- City of Lincoln

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission with Platte Basin Timelapse Saline Wetlands